|

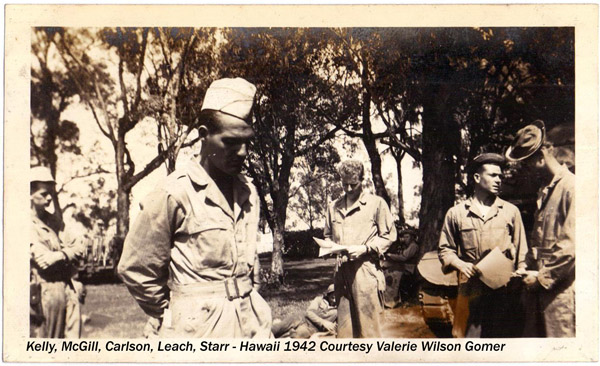

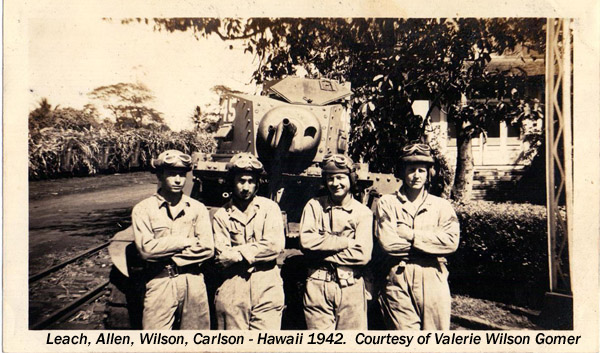

Colonel James H. Leach -

"The sweetest man who ever lived,"

Marion Leach, 2007

Colonel James H. Leach was born in Houston, TX on April

7, 1922. He began US Army service when he joined the Texas National Guard

on June 19, 1938 at the age of 16.

When Gen. Patton began his summer dash across France in

1944, Jimmie Leach was commander of Company B, 37th Tank Battalion, 4th Armored

Division, serving under the legendary Lt. Col Creighton Abrams. He had

trained for four years as a tanker. He was uniquely prepared.

Jimmie was wounded five times in Europe, received the

Distinguished Service Cross for his heroism at Bigonville on Dec 24, 1944 and

three days later he captured and guarded the entry of the 37th into Bastogne in

relief of the 101st Airborne.

After WWII, Jimmie served in Korea on the island of

Cheju, moderating the angry wrath among island natives, off-island Koreans and

returning Koreans who had served in the hated Japanese Army.

He married Marion Heirs Floyd in 1951 and spent four years in

Germany guarding the Fulda Pass against the seemingly inevitable roll of Russian

tanks west into the Rhineland.

He assumed Armored Brigade Command as a Colonel in

the late 1960's, was assigned to Vietnam as senior advisor with the 5th ARVIN division,

then, in 1969 assumed command of the 11th Armored Cavalry, replacing George

Patton III His aggressive leadership of the 11th is still remembered with

awesome respect by his subordinates and his peers. For the second time, in

his second war he heard the report that, "Jimmie Leach is the bravest man I ever

knew."

Jimmie Leach led the Army's Armor Branch with skill and

compassion in the early 1970's, managing the portfolios of some 6000 Army officers.

Men like Gen Fred Franks and the current Secretary of the Department of Veterans

Affairs, Gen Eric Shinseki, report that Jimmie was responsible for their very

careers as he fought to keep these future General Officers in the Army although

each had lost a limb to wounds in Vietnam.

His defense of one young officer earned him the enmity

of Gen William Westmoreland and he was passed over for promotion as General

Officer. His son describes the scene at his home, with great friend, Gen

Creighton Abrams on hand offering support, but not interfering with this final

decision, as a wake.

Jimmie Leach retired from the Army and worked for

Teledyne for 13 years from 1972-1985. He kept his service to the Army

paramount and carried out the legislative and financial work leading to the

United States Armored Forces Monument near Arlington National Cemetery.

Jimmie Leach now lives in South Carolina where, over

the last twenty-plus years he has supported the causes of soldiers and

soldiering with unflagging zeal. He has visited the battlefields of France

and the Ardennes more than ten times, placing monuments and memorials to the men

who came there with him - and never came home. He has made peace with his

enemies in Germany - and Vietnam and traveled through both South and North

Vietnam to relook at the places and events there.

Jimmie works hard still to effect the expansion of the

Beaufort National Cemetery in Beaufort, SC, a cemetery established under

President Lincoln whose growth is threatened by neighborhood encroachment.

In 2006, Jimmie Leach spoke at the James H Leach

ReadinessCenter, a new SC National Guard facility built with funds wrested

from Congress through Jimmie's unremitting pressure on the late Sen. Strom

Thurmond. He reminded the local Guardsmen, who were on their way to

Afghanistan, that they continued a proud National Guard tradition of more than

two centuries, to which he had been attached for nearly 70 years. And his

message was clear: soldiers must train for war and never become complacent

with the present situation.

Jimmie Leach and I have spent hundreds of hours

recording his story. In September 2007 I was with him in the Galt Hotel in

Louisville when a middle aged man approached me and said, "Is that Col. Leach?"

I said yes and he said to Jimmie, "I want to thank you for saving my life in

Vietnam."

Col. James H Leach died at 87 on Dec. 17, 2009.

He was driving his car near his home in South Carolina when he suffered a heart

attack. He was with us for 32031 days. Very few of them were wasted.

jimmieleach.us.

Matt Hermes

Copyright 2009 Matthew E Hermes

|

4. United

States Army

(An excerpt from Tanker Jimmie Leach. In this brief

segment Jimmie Leach describes his entry into the Regular Army, his graduation

from High School as a Sergeant and the training for war.)

I n September 1940, the 36th

Infantry Division was activated. Jimmie Leach was entering his senior year in

high school and was a buck sergeant now, and a tank commander. Mobilization was

expected to take the rest of the year; the 36th would leave Houston

in January 1941 just as soon as the tent city was complete at Ft. Benning, GA.

The tank company drilled a couple of times a week now in anticipation of their

departure in contrast to the monthly formations before activation.

“This

created a dilemma, having dropped out of high school for a year because of the

depression, I was now to graduate in the summer of 41 and here my unit was to go

on active duty in January 41. So I went to my principal and my dean and I told

them I was going to go with my unit when they were mobilized come hell or high

water. And could you, by chance, set up a battery of tests for this dummy that

would let him take this exam and let him come back on furlough and graduate with

his class. And I did that.” The 36th took off on the train for Ft. Benning.

They moved into a tent city and joined other units, “Just like us,” Jimmie

said. Each company of their new Battalion had the same equipment– only 2

tanks and 2 trucks. The Battalion A Co. was from Forsythe, GA, B Co., Ozark, AL

and D Co, Denver, CO. They represented the 31st, 32nd, 45th

and Jimmie’s 36th Infantry Div.

But

Jimmie got back to graduate with his HS class and by that time he was a staff

sergeant: platoon sergeant, tank commander in the United States Army. And he

graduated in his uniform, likely the finest looking graduate in his class. “I

came back – as a Staff Sergeant. Mobilized as a buck sergeant, came back as a

Staff – it was a great honor. My furlough said, Purpose: To Graduate from High

School,” Jimmie said.

Jimmie’s

new unit, the 193rd Battalion (Light) took part in the Tennessee

maneuvers of 1941. These peacetime maneuvers that crisscrossed rural Tennessee,

North Carolina and Louisiana in 1940 and 1941 were established by Gen George C.

Marshall to provide combat realism by combining large unit field training with camp and academic training.

Senior commanders and staffs carried out the elements of combat. This was a

laboratory on the grandest scale. New tactics, new organizations, new equipment

– and new leaders emerged from the maneuvers. Gen George Patton was one of

these. He spoke to his men:

“I want to

bring to the attention of every officer here the professional significance which

will attach to the success or failure of the 2d Armored Division in the

Tennessee maneuvers. There are a large number of officers, some of them in high

places in our country, who through lack of knowledge as to the capability of an

armored division are opposed to them and who would prefer to see us organize a

large number of old fashioned divisions about whose ability the officers in

question have more information. It is my considered opinion that the creation

of too many old type divisions will be distinctly detrimental and that the future

of our country may well depend on the organization of a considerably large

number of armored divisions than are at present visualized. Therefore it

behooves everyone of us to do his uttermost to see that in these forthcoming

maneuvers we are not only a success but such an outstanding success that there

could be no possible doubt in the minds of anyone as to the effectiveness of the

armored divisions. Bear this in mind every moment."

http://www.jumpingfrog.com/images/photo-war/phot5180a.jpg

Jimmie Leach looks at the overturned light

tank. “My M2A2 May West light tank hit a knee-high stump flipping us over on its

side. I leaped out of the command turret, called up another tank to put a

cable on us righting us rather quickly. After checking to see if I still had

plenty of engine oil we continued on our exercise.” Tennessee maneuvers taught

tankers like Jimmie Leach not to run into stumps, saving them from the

embarrassment of doing so under enemy fire. The 2d Armored sent a dedicated

Captain to guide the National Guard Commanders in becoming battalion tankers

instead of the single tank company they had been in Alabama, Georgia, Texas and

Colorado.

The

Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on the 7th of Dec., 1941. The

readiness, the training, the preparation for the unspoken thrill and horror of

war was about to come to its inevitable fruition. Some men would survive, some

would die. That was the only truth, the rest was a mystery. A snapshot of the

United States Army on Pearl Harbor Day finds less than 2000,000 soldiers.

The Army

exists to defend the Nation and to protect its interests. We

may forget in 21st century emphasis on foreign war that the Army must

defend our homeland; in 1941 that included 3 million square miles of the

continental United States, the Territories of Alaska and Hawaii along with

Puerto Rico, Guam – and the Philippines. On that Sunday morning the Army was

spread thinly off the shores of the continental United States. Small units were

stationed in Bermuda, Iceland, Trinidad and Newfoundland. Coastal defense units

sheltered the Panama Canal. Army regiments defended Kodiak, Juneau and

Anchorage in Alaska. The Puerto Rico National Guard protected its home island.

The Army defended Hawaii and Pearl Harbor but the events of that sunny Sunday

morning indicated the mission of defense the Army shared with the Navy had

failed. The important exception to the sparse population of overseas Army was

The Philippine Islands. Gen MacArthur had more than 20,000 US Army troops along

with nearly 12,000 Philippine men and women under his command. And one infantry

regiment and four artillery regiments were at sea, heading for the disastrous

campaign that would end with the decision in Washington that the Philippines

could not be defended. Gen. Douglas McArthur left the islands in March 1942 and

the bulk of the defeated Army, 10% of the Pearl Harbor Day Army headcount, died

or was captured and remained at the mercy of the Japanese for more than three

years.

After

December 7, the 193rd Tank Battalion (Light) consisting of four

National Guard Battalions was quickly assembled at Ft. Benning, destined for the

Philippines. They were back about 24 hours from Tennessee maneuvers. Jimmie

Leach relates they were tired as hell. The Captain said, “Park your vehicles,

we’ll wash them tomorrow.” Well tomorrow was Sunday, December 7 and the men

were sleeping in a little late and were awakened by the word of Pearl Harbor,

wherever that was and they were at war whether we liked it or not. Within nine

days the Battalion turned in its old light tanks with the machine guns only on

them, turned them in to post ordinance at Ft. Benning and drew, 17 tanks per

Company, about 70 tanks all together and these were the M-3 .37mm tanks with

five machine guns, one on each sponson and one bow gun. “Readiness?” Jimmie

said, “The Company that I was in, and all the Companies in that Battalion only

had a few men that had ever ridden in an M-3 much less fired the gun or knew

anything about the 37.”

First

Sergeant Hall had been to gunnery school at Ft. Knox. Staff Sergeant Leach had

been to gunnery school at Ft. Knox. Corporal Kelley had been to gunnery school

at Ft. Knox. “Six months earlier they are back with our old Mae West tank,

running like hell for leather, but not very combat ready it seems. We turned

those tanks into post ordnance and drew these new tanks. New to us, not new

tanks, but new to us. `And we outfitted our Division and the 2nd

Armored infantry troops loaded our tanks onto flatcars and chocked them down for

us while we readied our personal equipment and we got on the train. Hell the

tanks weren’t identified yet by Company. Which tanks belonged to what Company.

As quick as a tank was ready: new tracks, a new engine, new transmission, new

road wheels, whatever it needed, the 2nd Armored drove it up on the

damn train and chocked it down and we threw all the guns and equipment inside

the tank.”

They left

Ft. Benning; the mission was to go to the Philippines. Readiness? The

Battalion was far from ready. En route at Camp Polk in Louisiana they pulled

into a siding and a new Lieutenant by the name of Bob McGill joined the

battalion. “I’m new to this light tank business; I don’t know anything about

it. How long have you all had’em?” he asked. “Got ‘em yesterday, sir.”

“Good God.”

“That’s

what we thought too,” Jimmie Leach remembered in a talk he gave 65 years later

to a group of Guardsmen headed for Afghanistan. “Three of us had to gone to Ft.

Knox gunnery school and we had a PFC with us from a light tank unit of the 2nd

Armored Division. So we buttonholed him and got the manual out and we were

bouncing along the railroad on the way eventually to the Philippines and we

brain-drained that guy as best we could to refresh our memory and then on the

moving train, gong to San Francisco, across our country, the four of us went out

and we got on a tank and we would open a breech and close a breech and assemble

a breech and all the things you had to do. We did have ammunition. We had 37

mm rounds but we didn’t have .30 cal rounds. Then a boxcar on our train. Each

company had its own loading detail, hand cranked, one bullet at a time going

into the damn web belt. A tedious job and they were loading all ball

ammunition. No tracer. No shot. Just ball which was not acceptable in combat.

That loading detail worked all the way across the country.

“Now, as

we four people, mastered the tanks more or less, we took our crews, one at a

time with each one of us trainers and we trained our soldiers en route to war.

My God it was frightening to think of the potential of this."

They left

San Francisco anticipating the long voyage to the Far East. “We now we had

about 12 tanks on the top of the ship. On the top deck. The rest of them were

in the hold. We manned the tanks. We shot at whitecaps in the waves. We had

37 mm shot; that’s all we had. We fired the gun and a number of the tanks went

into recoil but the barrel failed to return to battery because the gun shields –

they had four bolts holding the gun shield on and they were slightly tapered –

and when the gun came back the taper prevented it from coming back to battery.

That minute taper prevented the gun from working properly.

“So if we

had gone to war and landed in the Philippines in this condition we would have

gotten one round off! That’s all. God was with us. As we were on the Pacific

heading for the Philippines, the US government wrote the Philippines off and

diverted our convoy to a place called Oahu Territory of Hawaii. They diverted

us in there and 30 days to the day we pulled into Pearl Harbor and the city and

harbor of Honolulu and they marched us up to Schofield Barracks, and we put a

tank Company at Mauna Loa Park, one at Barbers Point, one at Beluga Point and we

patrolled the island with our light tanks. We found there though a tank

Company with the Hawaiian Division. And they had the same tank we had had, the

damn Mae West tank. And that’s all Hawaii had. But we absorbed that unit and

it kept their light tanks because we didn’t have any replacements for our own.

“But now

we had guns that wouldn’t go back in battery. A number of them. Too many of

them. So we had to pull the gun shields off. We didn’t have any good square

bolts to hold them. And we had to bore a bigger hole in the armor! Scraped

them back and forth and eventually we were ready to go.”

Five months into Hawaii, the Captain’s

striker, Mortimer Hirsch, came over and said to Jimmie Leach one Sunday

afternoon, “The Captain is in his quarters and he wants to see you.” Leach and

Hirsch went to the Captain's quarters in Schofield Barracks. The tanks were parked in the

quadrangle in front of the barracks yard but the people had gone home already.

The Captain had a little nip on a Sunday afternoon and Jimmie said no thank you

and the Captain said “God Damn it Sergeant, have a little drink,” “Yes sir,

thank you very much sir.” So he did. They were talking about the platoon with

2nd Lt. Wayne Sikes and another officer but the second officer left

the room for a few minutes “First thing I knew one of the Lieutenants there had

disappeared and he came back with a blouse on his thumb and he said, ‘Leach,

stand up.’ And I did. He handed me the blouse and said, ‘Put this on’. It was

a 2nd Lieutenants blouse. A dress uniform blouse. I put it on and

looked in the mirror. It had 2nd Lt. bars on the shoulders and tank

insignia on the lapels and I am looking at this 2nd Lt. uniform with

Staff Sgt. Leach in it. And Earl Douglas, Captain Earl Douglas said, ‘We’re

going to send you to Officer’s Candidate School at Ft. Knox. You’ll

make a good officer and we want you to go. You earned it.’ So I went back,

ballooned, I was so taken by that. And so Jimmie Leach was ready to go to Ft.

Knox,” Jimmie said.

There was a problem. Jimmie Leach needed a

birth certificate. The Army knew him as 22 year-old Jimmie Leach. But he was

20 and his name was James Herbert Shipps. “I wrote mom,” Jimmie said. “I need

a birth certificate, mom, but I need you to adjust it and make me two years

older. She said, ‘I can’t do that because I wasn’t married at the time you want

the birth certificate to state. So you have to take it like it is.’ I ran a

notice in the Honolulu paper, any claims against James Herbert Shipps or James

Herbert Leach, let it be known. No challenge. So I applied for the name

change, to be officially Leach and Gov. Poindexter of the Territory of Hawaii

signed off on the name change and my military record was back where it ought to

be. The military never questioned my age, never."

(An excerpt of a work in progress)

6/12/09

Questions or comments: Contact Matt

Hermes

|

![]()